Gender Materiality

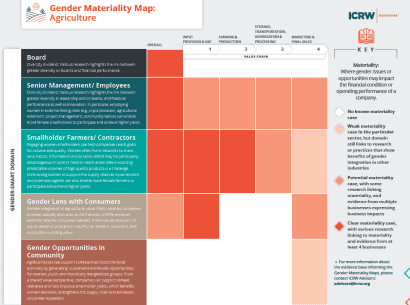

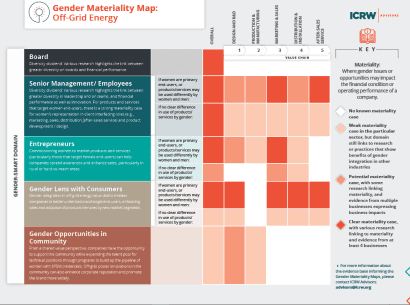

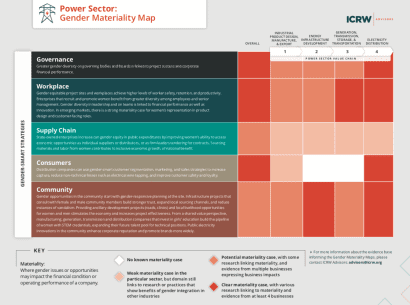

ICRW’s sector-specific Gender Materiality Maps outline where gender integration is most “material” for businesses, by sector.

Identifying where and how gender may be material in a sector helps companies understand and assess gender-related risks and opportunities that are reasonably likely to impact their financial condition or operating performance.

The Gender Materiality Maps drew inspiration from the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) Materiality Map, an interactive tool for corporate and investor use that identifies and compares disclosure topics and their financial materiality across different industries.

-

What evidence is there for gender materiality?

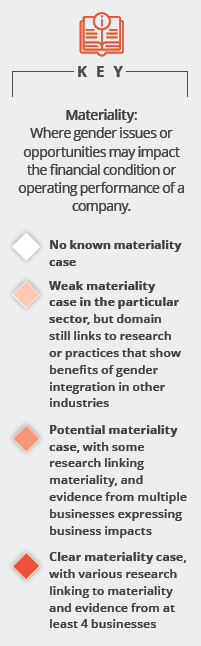

Our Gender Materiality Maps are based on specific business-level evidence. In the left-hand column are domains in which the use of a “gender lens” may impact business outcomes. Moving left to right across the Map, the strength of the materiality argument is depicted at each step in the sector value chain by the above color scale, with darker shades indicating stronger materiality.

Our Gender Materiality Maps are based on specific business-level evidence. In the left-hand column are domains in which the use of a “gender lens” may impact business outcomes. Moving left to right across the Map, the strength of the materiality argument is depicted at each step in the sector value chain by the above color scale, with darker shades indicating stronger materiality.

The lightest shade of orange indicates weak materiality in the particular sector, with research or practices in the domain area showing the benefits of gender integration in other industries. The medium shade represents a potential materiality case, with some research in the sector linking materiality in the domain area and evidence from multiple businesses expressing impacts. The darkest shade of orange links to a clear materiality case, with various research linking to materiality and evidence from at least four businesses.1

Evidence used to determine potential for financial impact has been drawn from studies, reports, and interviews with companies in the relevant sector. In some instances, the materiality case cites global research that spans multiple sectors, such as evidence for the materiality of women’s board and workforce representation within international corporations. While ICRW recognizes that impact investors targeting developing and emerging markets often invest in small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), evaluative data2 of gender integration in SMEs is still very limited. Hence the current evidence base may draw on multi-sector research or data from larger corporations in related industries.

1 Please contact [email protected] specific company-level data backing the Gender Materiality Maps.

2 Evaluative data includes empirical research confirming a strategy’s impact(s) on key performance indicators, for example through return on investment (ROI) and return on equity (ROE) studies, impact evaluations, or randomized control trials (RCTs). -

Is broader diversity material to business?

Implementing gender-smart opportunities in tandem with diversity and inclusion efforts recognizes the unique value addition of the intersectional diversity dividend—leveraging the view points and contributions of a broader and more (socially, ethnically, generationally, experientially) representative workforce.

A gender lens can be particularly useful for including women who have been excluded from areas of the formal economy. However some women experience other intersecting forms of discrimination in addition to gender biases. To be more diverse and inclusive, companies can intentionally engage women (and men) who are members of historically marginalized1 groups, such as ethnic minorities or people living with a ‘dis’ability.2

Intersectional gender diversity may especially benefit companies. For example, in international social enterprises, strategies to increase the number of not only women, but indigenous women, on boards and in senior management can contribute to organizational sustainability in country, contextualized decision-making, and other strategic outcomes. Beyond counting women, diversity efforts consider how workplace dynamics are affected by other factors such as nationality, ethnicity, legal identifiers, and age. By bringing more voices to the table, workforce diversification can lead to qualitative improvements such as greater innovation, team cohesion, and employee satisfaction. While these may not prove financially material in the immediate, they are valuable organizational enhancements that are often considered proxies for business impacts to come.

Assess company performance on numerous aspects of diversity by using the supplmental Diversity Data Survey, found in Tab 2 of the offline versions of our Gender Scoring Tools.

1 'Historically marginalized' indicates a person or member of a group that has been discriminated against in the past and/or is currently disadvantaged due to one or multiple factors. Affected groups will vary by context, and can include known or unknown identities. For example, historically marginalized people may be ethnic or religious minorities; refugees or war returnees; people living with terminal illness, physical or intellectual disabilities; very elderly or young people; people who have been homeless or formerly incarcerated; people who are gay or transgender; or individuals who experience multiple forms of social marginalization based on their intersecting identities.

2 ‘Dis’ability refers to a condition or function judged to be significantly impaired relative to the usual standard of an individual or group. The term relates to individual functioning, e.g., physical impairment, sensory impairment, cognitive impairment, intellectual impairment, mental illness, and various types of chronic disease. -

Is materiality generalizable, or specific to companies?

Gender is actively constructed, with dynamics between women and men that are negotiated in each society and organization.

Given gender’s specificity to context and the particular value chains investigated in the Gender Materiality Maps, it is key to remember “materiality is not subject to bright line rules.” As the U.S. Supreme Court has defined it, the “determination of materiality is an inherently fact-specific finding” in which what is material for one company is not necessarily material for another. The ICRW Gender Scoring Tools are thus a critical first step in assessing how a specific company is performing and where gender considerations are reflected in the “total mix” of factors affecting materiality.

The Gender Materiality Maps also enable investors to review where scores are lower but materiality is higher, in order to prioritize gender opportunities. If a company scores lower in a gender-smart domain where materiality for the sector maps higher, a customized gender action plan and technical assistance may be especially valuable next steps. Where financial materiality is weaker, or the enterprise is early-stage, grant funding can be a relevant financial instrument for integrating gender to harness social and economic impacts (see our Social Impact Visuals).

Like other sustainability reporting initiatives (e.g, SASB), scoring various gender-smart aspects of business allows investors to evaluate and compare companies’ performance in a given area, and eventually with the aggregation of sufficient data, benchmark against industry peers. Ultimately companies decide what is financially material and which gender-related information should be disclosed, taking into account legal requirements, trends in ESG reporting (i.e., on environmental, social and governance indicators of sustainability), and their own interest in disclosing gender data alongside peer companies in the sector.