Evaluation Results From the (Re)solve Project

2021

Family planning (FP) plays a uniquely powerful role in enabling women and men to achieve their desired family size and build more equitable societies. And yet, global family planning programs remain at risk due to funding gaps and limitations in assumptions about what prevents women from using contraception.

Family planning (FP) plays a uniquely powerful role in enabling women and men to achieve their desired family size and build more equitable societies. And yet, global family planning programs remain at risk due to funding gaps and limitations in assumptions about what prevents women from using contraception.

In this context, the (re)solve project used data on and insights into women’s and girls’ barriers to contraceptive use and nonuse to design and test a unique solution set in three focus countries: Bangladesh, Burkina Faso and Ethiopia.

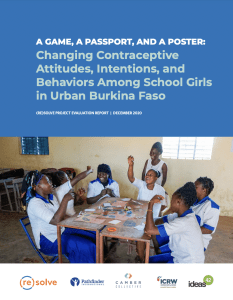

In Burkina Faso, where the project focused on unmarried girls, this solution set consisted of a participatory board game (La Chance) that corrected myths and misconceptions and increased pregnancy-risk perception; a health passport that eased girls’ access to health facilities; posters in health facilities that normalized consultations for adolescent girls; and name tags that identified youth-friendly health care providers. Participating health care professionals were also trained on how to provide youth-friendly services and oriented them to the solutions and their rationale.

The following report provides the evaluation results from the (re)solve project in Burkina Faso:

Key Findings:

- The (re)solve solution set was found to be highly acceptable among adolescent girls and other key stakeholders, including health facility staff, game facilitators, and ministers.

- We found statistically significant differences in contraceptive attitudes and beliefs at endline between intervention- and control-school girls.

- A sizeable number of intervention-school girls went to a health facility for sexual and reproductive health (SRH) information or reported an intention to visit a health facility.

- We saw a positive relationship between exposure to the intervention and intention to use contraception in the next three months, although it was not statistically significant.

Key Recommendations:

Based on initial indicators of success, we see potential for expanding the (re)solve solutions to other schools and new audiences, such as older and younger girls, out-of-school girls, and boys. Program participants echoed similar calls for replication and expansion. The intervention will need to be further contextualized and adapted to the needs of each new group, and additional formative research may be required. The board game, passport, and posters might need to be re-designed to reflect the behavioral bottlenecks new audiences encounter. Future evaluations will be needed to understand how the intervention differentially affects these diverse groups.

While the intervention shows promise, we do not know if playing the game more than once could amplify the effects. We also do not know if and how COVID-19-related school closures and movement restrictions affected girls’ ability to access health facilities and how the pandemic might have altered SRH behaviors and risks.

Finally, implementation of (re)solve solutions at scale will require close coordination between and oversight of the Ministries of Health and Education to ensure successful integration and implementation. Behavioral solutions like the game, health passport, and poster can complement existing demand-generation interventions and connect girls to youth friendly health facilities so they can make informed decisions that benefit them.