The war at home: uncharted territory

Media Contact

“It’s normal, being beaten, yelled at…Some of us are used to it just like the way we are used to eating Ugali.” – female focus group participant, referring to a staple of the Tanzanian diet

Jua* is a 25-year-old Tanzanian woman with a violent husband. He beats her when he’s angry. He blames her for making him angry and “forcing” him to beat her. Tragically, Jua’s situation is not uncommon. More than a third of Tanzanian women report experiencing physical violence at some point in their lives, while nearly half of all women in predominantly rural areas like Iringa and Mbeya are affected.

What sets Jua apart from more than half of all Tanzanian women who experience violence is that she actually seeks help. Yet of those who do seek help, most turn only to their family members or close friends rather than local authorities or the police.

What is it that prevents women in Jua’s situation from reporting domestic violence? A fellow ICRW researcher, Sophie Namy, and I recently set out to answer that question in collaboration with representatives from EngenderHealth’s CHAMPION Project and researchers from the University of Dar es Salaam. Through participatory focus groups with community women and men, we heard over and over again that the physical violence Jua experiences every day is largely seen as a given part of marriage.

Women come to expect – and even accept – this violence because their elders, family members, and peers overwhelmingly tell them to. It becomes so normal, that for many it’s just like eating Ugali, a corn-based staple in Tanzanian meals, as one woman told us. Acceptance of violence is so steeped in traditional values that even forced sex within marriage or intimate relationships is not viewed as an offense that can or should be reported. Women are taught that a “real wife” will keep silent about the abuse to avoid the shame of revealing secrets that are “family matters.”

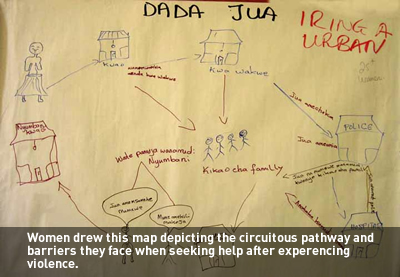

With the pressure to keep silent, women like Jua who decide to share, report or seek help are brave. But this courage isn’t always rewarded by the people and systems around them. Jua first goes to her parents for help, but she is quickly sent back to her in-laws to settle the issue because they’re “her family now.” The in-laws in turn arrange a series of family meetings, where the beatings are acknowledged but the focus is on reconciling Jua with her husband. When the violence continues, Jua tires of this routine and goes to the police. From the police, she’s sent back to the family for another attempt at reconciliation. Or, “if she is hurt,” Jua may go to the hospital. And the cycle continues.

The circuitous pathways that Jua – and many other women – has to navigate to seek help through formal channels like health care providers and the police are not designed to respond to the needs of women who experience violence. Even informal sources of support, such as family and social networks, tend to focus on keeping Jua’s marriage intact rather than getting her the help and protection she needs to live a life free of violence.

When communities keep silent about this violation of women’s right to live without violence, it creates an environment where more women will suffer in silence, frustrated by the failure of social and government structures to support them. The importance of removing the barriers that prevent women in Tanzania from seeking help and receiving appropriate care can’t be overstated. It’s critical to their well-being and that of their families and society.

Our research team has put forward a number of recommendations about how to eliminate both social and structural roadblocks so women like Jua can seek justice and attain the care they deserve. To do this, efforts must include community awareness campaigns stressing that no kind of violence against women is acceptable, even within relationships; and that survivors should not be blamed or stigmatized, but rather, supported. Meanwhile corruption within the service provision system must be addressed and services for violence survivors need to be available close to women’s homes.

To achieve any or all of our recommendations will require the concerted effort of individual men and women, communities and decision-makers – at every level of society.

*Jua is a composite fictional character who represents many of the women we heard about during our research.

New research: The upcoming report, “Help-seeking Pathways and Barriers for Survivors of Gender-based Violence in Tanzania: Results from a Study in Dar es Salaam, Mbeya, and Iringa Regions,” summarizes the author’s finding and will be available in the coming weeks.

The series: This is the first piece in “The War at Home,” a series of blogs about domestic violence that will be featured throughout the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-based Violence, which runs Nov. 25 through Dec. 10. Read the next blog in the series, Enduring Evidence.