Uplift: A Conversation with Soraya Chemaly

Costs of Sex-based Harassment, Intimate Partner Violence, Men and Masculinities, Sexual Violence, Technology-facilitated Gender-based Violence, Violence Against Women and Girls

22 June 2021

Media Contact

June 22nd, 2021 | Uplift, a series: Conversations to raise awareness, lift voices, inspire

(Learn more about ICRW’s work on gender-based violence, intimate partner violence, men and masculinities, and sex-based harassment)

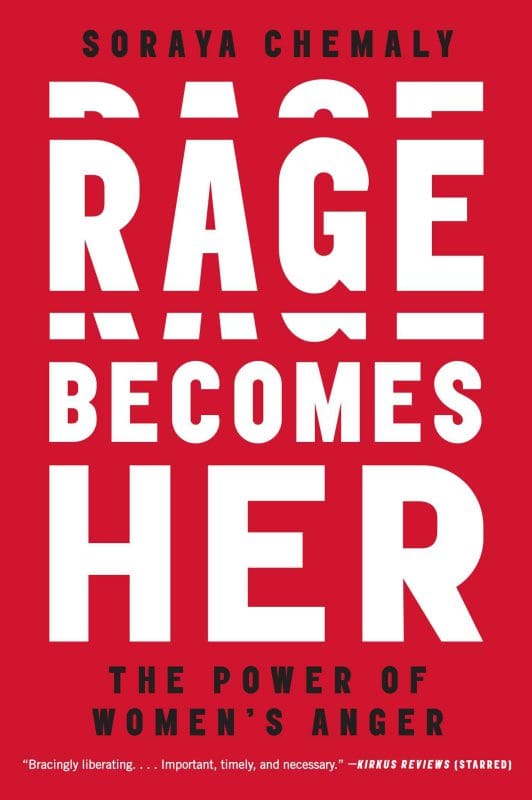

Soraya Chemaly is an award-winning author and activist. She’s the former Executive Director of The Representation Project and director and co-founder of the Women’s Media Center Speech Project, where she focused on increasing women’s civic and political participation. In 2018, Soraya published Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger, a topic she also covered in November that same year in her TED Talk, where she counters the socialization of women and girls to suppress their own anger and promotes it as a strength. Her work as a writer, speaker, and activist is featured broadly across media and academic research.

Soraya has won numerous awards, including the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication’s (AEJMC)’s Award for Feminist Advocacy, the Secular Woman Activism Award, the Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press’s Women and Media Award, and the Feminist Press’ Feminist Power Award. And Elle Magazine, in 2014, named Soraya among the 25 Inspiring Women to Follow in social media.

Recently, we caught up with Soraya for an interview.

Soraya, thank you so much for joining us for this Uplift series interview. In 2019, you took part in a panel at ICRW on technology-facilitated gender-based violence (TFGBV), which is the use of tech to harass, defame, or exploit. Now, you’ve done a lot of work to disrupt the silencing of women on- and off-line and to ensure full civic and political participation and freedom of expression. But online GBV is so pervasive and can be relentless. Given that, have you seen breakthroughs in your work?

SORAYA: Yes, I think I have seen a lot of change happening in the last four or five years. It seems that more people and institutions are understanding the connection between the harassment of women – both online and off, but online in particular – as really a reflection of degradations of our political lives and democracy instead of, as previously, problems that women needed to take care of privately – the way we’re generally “supposed” to take care of violence that we encounter in homes or on the streets. So, I think I’m a little hopeful about that. I do think it’s a good change.

You talk in your book, Rage Becomes Her, and also in your TED Talk about the important role anger plays in shifting power dynamics and tipping the scales on gender inequality. In Rage Becomes Her, you say, “the truth is that anger isn’t what gets in our way – it is our way. All we have to do is own it.” That is a powerful statement, but how does a woman own it when, from a very early age, she has been taught to contain it, to extinguish it? That is not an easy shift to make.

SORAYA: It’s not an easy shift at all, and I don’t want to imply that it is. But I do think it’s an important shift. But first, for women, as individuals, to admit – even at the most basic level – that they are angry and use the words to label those emotions so that they can then think about what to do next. So, I want to be careful about saying this isn’t about the violent expression of rage because you know we have these images of rage – really, frankly very masculinized in terms of explosive, destructive rage – but that’s also dysfunctional anger. That’s not what I mean. What I’m trying to describe is women who might say they’re tired or frustrated. We learned to minimize this emotion of anger, but to not do that anymore, to not sublimate it or divert it or let it suffuse their bodies in ways that are unhealthy. Rather say, ‘You know what? I’m angry, and I have the right to share this with the people around me who theoretically care for me and love me,’ and see what happens.

“Anger,” you write, “is an assertion of rights and worth. It is communication, equality, and knowledge. It is intimacy, acceptance, fearlessness, embodiment, revolt, and reconciliation.” Above all, you say, it is “a gift to yourself and the world that is yours.” This is a far more nuanced look at anger, one that runs counter to what many of us learn growing up, where anger, sadness, joy, disgust, envy exist almost independently – as if the light goes off for one when another goes on. You talk about how anger is actually more integrated in the fibers of our being and in all we do – and, taking it a step further, are essential. Soraya, when did you start to see your anger as a gift and as a powerful tool?

SORAYA: That’s such a great question. Probably not until my mid-forties. I was a person who, probably earlier in life, would have easily said, “No, I’m not angry at all. I don’t get angry.” Anger was really disparaged in my childhood and in our culture. But then, I really felt quite isolated, which is actually kind of ironic because we learn that anger is what causes separation and isolation because it threatens to break relationships – and women are not supposed to do that.

In fact, what’s isolating is keeping these important thoughts and feelings to yourself. It degrades intimacy. It makes it difficult to make change. And it makes people unhappy.

And so, I realized that every feminist community that I belonged to – every one of them was filled with creativity and drive and ambitions for the future – all of them shared the quality of people who had gotten angry. And I think that was really an important lesson.

In some of your work, you have focused on countering gender norms that hold us back – and even create harm. But beliefs and behaviors are so deeply entrenched. How can we go below the surface and make that change happen?

SORAYA: Beliefs and behaviors are, in fact, deeply entrenched. I kind of only jokingly say that everything has to change all at once all at the same time everywhere. It’s just a very long process, and I think people need to work where they can. So, we have people looking at early childhood education and people looking at adolescents and people looking at economic lives and people looking at political realities. And it all has to happen. We need to be not just thinking about these beliefs and behaviors or challenging these beliefs and behaviors or exposing them or illustrating them.

We need to be thinking about new beliefs and behaviors that are healthier, more egalitarian, more democratic.

These past couple of years have been very challenging – and even devastating – for so many people around the world. COVID-19 and the economic fallout from the pandemic. A rise in domestic violence. An increase in virtual platform use, predictably met with a surge of online harassment. Deepening wealth gaps. It’s not like these inequities were not there before, but rather, were amplified. For many, these past two years have been real setbacks. Soraya, what keeps you going? What gives you hope?

SORAYA: That’s a good question. I don’t know that today is [laughs] the best day for me to answer it. My husband jokes that, in order to do this kind of work and to be an activist, public feminist person, you have to be a daily pessimist but an eternal optimist. I think that’s actually very true. None of us would be doing this work if we weren’t fundamentally hopeful and if we didn’t believe that the future can be different and can be better for more people. What I find interesting is, you know, a lot of things that we identify and talk about – the hard things, the ugly things, the unfairness, the injustice – they’re really traumatic. They’re traumatic to individuals. They’re traumatic to societies. And we don’t think of trauma temporally. We don’t think of it in terms of what it affects in terms of the future. We tend to focus on the past in order to understand it. But in fact, trauma is a theft of the future because people are so debilitated that they can’t even envision it.

What gives me hope is just the sheer number of people who have had terrible experiences, negative experiences, life setbacks – not in terms of some random event but just the circumstances of life and oppression and disparate impacts of identity – and how they can envision a better future. That’s enormously powerful and hopeful. Particularly, I’m in awe of a lot of very young people who really understand that they have a kind of power that, frankly, a lot of people don’t want to recognize, and they don’t care. And I think that’s really terrific.

More about Soraya:

Visit Soraya’s website, and be sure to follow her on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn.